My second MA project presents a model of sustainable design practice rooted in the commons and acts of commoning.

Recent years have seen a proliferation of work on the commons as a field of ‘social study’1. The concept of reclaiming commons in order to own, use and protect our shared common resources collectively (referencing the history of common lands in feudal Britain, Enclosures, Tragedy of the Commons etc) has much to commend it, in the sense of removing boundaries (literal and metaphorical) to be able to responsibly manage and protect the planet.

The marketization and direct theft of land over centuries have eroded the commons2 so that they are no longer available to everyone. With a present-day raised awareness of the climate crisis and the dangers faced if we no longer have what is seen as essentials to living: land, water, clean air, natural materials etc. the need for this work feels more urgent than ever.

The commons, or commoning, has the potential to become a new social movement and, through new social practices, a route to a sustainable future on earth.

This movement presents itself at the edge of or, even, outside of the existing social paradigm of western societies. It is counter to the widespread exploitation of our global natural resources by the neoliberal establishment and corporate businesses. In other words, the exploitation of the commons. Although most land today (including common land) is privately owned, and therefore, not always accessible to the public, the commons could, or more importantly, should belong to everyone. They are part of our natural inheritance.

Can we begin to find ways to reclaim commons, with acts of commoning, in a time of increased ‘enclosure’ of public space? The urban commons (which I identify as shared urban public spaces) is the space the walk is principally engaged with. Public spaces, be they squares, civic amenities, footpaths and public access areas in towns and cities (where normally the state has control), can create active social spaces for cultural events, political action and meetings. They can be public or private, but can they be accessible to all?

Walking is the dominant commons in this model. As Gros states “the true direction of walking is towards the edge of civilized worlds… walking is setting oneself apart: at the edge of those that work, at the edges of high-speed roads, at the edges of producers of profit and poverty, exploiters, labourers, and at the edge of those serious people who always have something better to do than receive the pale gentleness of a winter sun or the freshness of a spring breeze”.3

Despite increased rights across the globe, women continue to experience life in a man’s world (Solnit, Criado-Perez). My aim with the model is to make women in a local community, creators in public space as well as potential designers of the future.

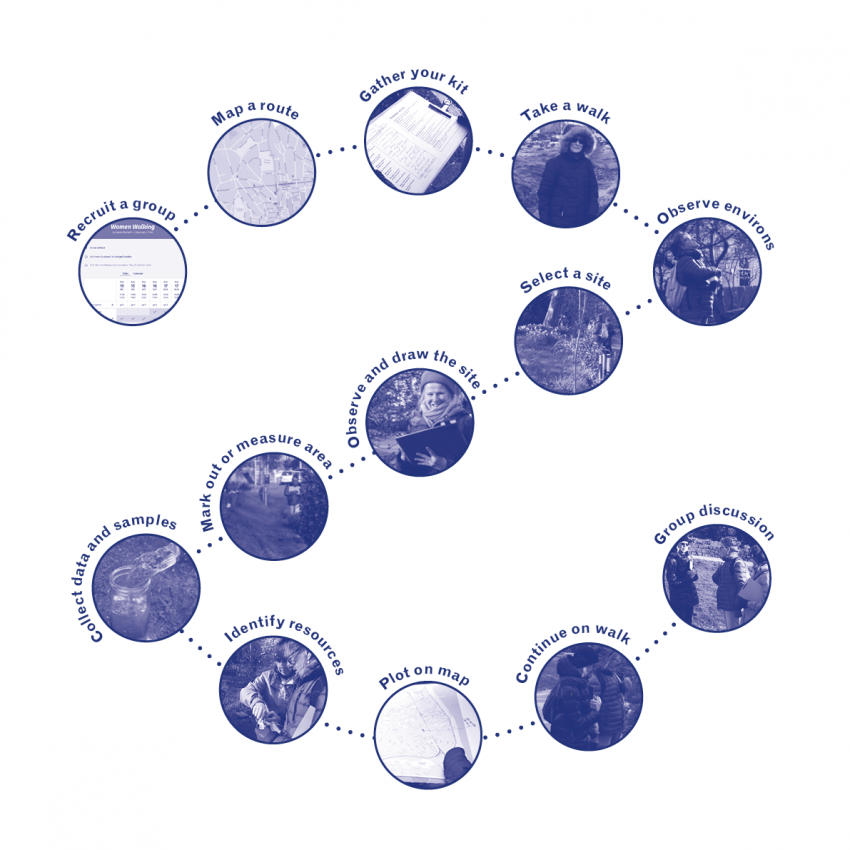

The model consists of a walk for women, the objective of which is to identify common land, currently underutilised, in the public domain for the common good, perhaps as community gardening projects. Other aspects of the commons (e.g. water, raw materials) may also be identified.

The walk involves participation, collaboration and information gathering. I want to observe how a group of women interact and ‘perform’ on the walk..

This model aims to activate women in our social spaces, potentially creating change in the places where they live and work. A strong influence Lefebvre’s radical vision for a city in which “users manage urban space for themselves, beyond the control of both the state and capitalism”4. For Lefebvre, users have a “right to appropriate what is properly theirs”5.

If space is for these commons of social relations, and walking and gardening are social acts and bodily movement, do these elements work well together in a single purpose?

Can this model of ‘walking women designers’ be widely used to empower women to take ownership and responsibility for areas of public space, to create a support network and shine a light on the importance of land ownership and the commons in general?

Interviews with participants can be heard here: https://vimeo.com/340197576

Notes

- Ruivenkamp, Guido, and Andy Hilton. Perspectives on Commoning: Autonomist Principles and Practices. 1, London: Zed, 2017,

- Wall, Derek. Beyond Commons Feudalism and Platform Capitalism, STIR Magazine Issue 20, Winter 2018

- Gros, Frédéric, John Howe, and Clifford Harper. A Philosophy of Walking. 94. London: Verso, 2015.

- Purcell, Mark. 2014. “Possible Worlds: Henri Lefebvre and the Right to the City.” Journal of Urban Affairs 36 (1): 141

- Ibid., 149